Dennis Butlers Grand Champion Plans Built Cozy III By David Gustafson

Dennis Butler’s Grand Champion Plans Built Cozy III David Gustafson Dennis Butler has had two careers, both in tandem and both enviable. The first, based on his degree in physics was working for a number of companies that were involved with NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston. That put bread on the table and gave Dennis a chance to rub elbows with astronauts and play with the space shuttle simulator. The second was his Cozy III. That’s where some of the money that didn’t go for bread went. It was an “endeavor” that took 20 years and kept him fascinated and involved all the way. This past summer he flew his Cozy to AirVenture and after winning a Silver Lindy last year, he took home the Golden Grand Champion Plans Built Award in 2012 for a homebuilt aircraft.

The two decades of learning and effort that went into Dennis’ project are a testimony to an individual who enjoyed learning as much as building and flying; to someone who never saw any part of the project as insurmountable; he just encountered each new skill requirement or aircraft system as an opportunity to learn, knowing he could master whatever it took to get the job done. Dennis admits that in the beginning he harbored “enormous respect for the people who really know what they’re doing,” and now he can count himself among those people who succeeded in doing it all. This was more than a simple assembly program, it required learning how to do everything from determining what materials he needed, to ordering them and eventually figuring out how to approach the first flight (with a little help from some of his friends).

Dennis originally wanted to build a Long EZ or Defiant (he was strongly enamored with the designs of Burt Rutan) , but before he could order a set of plans, Burt Rutan shut down RAF to devote full time to Scaled Composites. The only Rutan design that was still available was the Cozy, which Nat Puffer was selling under license with Scaled Composites. He ordered a set of plans from Nat and began a journey. There were times when the process had the effect of therapy. During most of the construction phases he was a projects leader for United Space Alliance, working on avionics integration and testing for the space shuttles. There was a lot of stress associated with that job and the Cozy gave him an escape.

Having studied photos of Nat and his wife, Shirley, inside the Cozy, and looked at the plans, Dennis set himself an extra level of challenge before he ordered a single part or piece of material. The original 3-seat Cozy was cramped, so Dennis decided to enlarge the design by 10 percent …in all directions. He redrew the plans and consulted with some of his friends in the space program. There were always plenty of engineers available for opinions and verifying. That of course eliminated any possibility of using any of the prefabricated parts manufactured by third parties. He made up a list of materials and began ordering from Aircraft Spruce.

At the time, Dennis, his wife, Margaret, and their son, John, were living in Rhode Island. Dennis was working in the basement. Then he moved to the Clear Lake, Texas to begin working at the Johnson Space Center and while a new home was being built for his family, they lived in an apartment. At this point, the fuselage “tub” or lower section, made an ideal coffee table. A few months later he moved the parts of his Cozy into a three-car garage that had an extra 12’ extension built onto the back of it. He had all the room he’d need and set to building work benches. Serendipitously, Dennis’ good friend, Jim Voss, owned a house across the street from him and was building a Long EZ. Jim became Dennis’ EAA Teechnical Counselor and Flight Advisor. Both men crossed the street frequently to help the other or seek advice.

The Cozy is a design that requires the builder to rotate the fuselage a number of times. It’s too big for one or two men to handle so Dennis hosted a series of “Aircraft Attitude Adjustment Parties”. He’d make up a batch of lasagna, invite 10 to 15 people to come over to his house for lunch and then flip the fuselage over before serving up Italian food. He did that 5 times over a dozen years and everyone enjoyed it. For Dennis, the biggest obstacle and one of the most interesting learning experiences was the firewall aft (the Cozy’s a pusher). Because of his enlargement of the design, he couldn’t buy a prefabricated engine mount. That meant designing his own mount and doing his own welding. He didn’t know how to weld. So he signed up for a three-month, $75 course at a technical college and learned how to handle an oxy/acetylene torch. “You don’t become a master in only three months, but it did give me a pretty good idea of what to do,” said Dennis. At the end, his instructor asked him what he was planning to do with his new skills and when Dennis explained, the instructor invited him to watch a demonstration of TIG welding. Dennis signed up for another 3-month, $75 course in TIG welding. “I wasn’t a master at TIG either,” said Dennis, “but by signing up for a third 3-month course and working closely with the instructor, I was able to complete the engine mount to my satisfaction.” He’d devoted nearly a year to that project, but had learned a lot about cutting, fitting and welding in the process. That’s what homebuilding is all about.

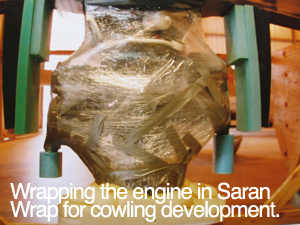

Dennis had purchased an IO-360 engine, overhauled by Aero Sport in Vancouver. To create a cowl for his Cozy, Dennis tilted the aircraft into a 90 degree up position (leaving the engine pointing down) and wrapped the engine in a kind of industrial Saran wrap. He covered that with duct tape, then made up hundreds of blue plastic plugs about the size of a wooden thread spool, which he glued to the duct tape. He filled in all of the spaces around them with pour foam and when the foam hardened, he filed and sanded it down to the tops of his blue plastic plugs. When all of the plugs were showing through the foam like so many polka dots, he created a mold for a fiberglass cowling that was close fitting and which eliminated potential engine cooling problems. The mold also allowed him to fabricate cowl parts that have a perfectly smooth interior. It took him about two years total to build the engine mount, hang the engine and make the cowl. In the process of making his wings, canard and fuselage, Dennis incorporated about between 70 and 80 mods to the plans Nat Puffer had supplied him with…in addition to expanding the design by 10 percent. Indicating that Nat made some pretty strong statements about changing anything, Dennis suggested: “I must have been Nat’s worst nightmare. But that’s the beauty of doing your own design and enjoying the freedom of creating something in the Experimental Amateur Built aircraft movement.”

In the process, Dennis designed his own landing lights, implemented an electric nose gear retract mechanism, reduced the configuration of the fuel tanks to provide more room in the cockpit (he still has 7 hours of fuel in economy cruise), and he created removable side panels that allow him access to control tubes, cables and wires (the original design called for permanent side panels which would have closed off the controls and wires forever). He also changed the shape of his canard. John Roncz had recommended putting dihedral in the Canard to Cozy builder Vance Atkinson. Dennis got a set of plans for that shape and built it. The dihedral creates better airflow between the canard and the main wing, enhancing performance slightly. When it came to the panel, Dennis preferred the old steam gages, over what was new at the time: glass panels and EFIS. What was available when Dennis was ready to outfit his panel was very expensive and he really wanted to put together an IFR panel for under $10K. In the end he went a little over that, but is very happy with the results. What caused him to have such allegiance to the steam gages? He’d learned to fly with them and finds them easier to read in dim light and turbulence. The only digital items in his panel are a GRT engine monitor, digital tach and chronometer. Toward the end of the project, Dennis moved into a large hangar that his Cozy would share with Jim Voss’ Long EZ, Charlie Precourt’s VariEze, Scott Horowitz’ Q200 and Byron Allen’s Cessna 340A. He completed the final assembly in that hangar. He and Jim prepared their airplanes for painting, disassembled them, moved the parts to a paint booth that they had build in Dennis’ garage, and got Mike Huff, a highly skilled professional, to do the spraying. With the completion of the upholstery, Dennis was running out of reasons not to take an active runway. “I made the first flight myself, and that’s always the wrong decision. Builders have too much tied up in a project and are likely to hang on when they should bail out,” he said. However, Dennis had access to a lot more test pilots than most of us do. NASA tends to attract them. He borrowed test pilot literature from some of his friends, sat in on a one-day EAA seminar on test flying your own airplane and watched an EAA film on test flying. This was in addition to consulting with a number of astronauts and certified test pilots. We should all be so lucky.

He’d done very little flying in the years leading up to the completion of his Cozy, and got together with a CFI to do some high speed taxi tests in a Grumman Cheetah. He’d lift the nosewheel of the Cheetah off the ground and then back off on the throttle. He got into his Cozy and did the same drill. Fortunately, he was at Ellington Field, a class D airspace and the tower was happy to work with him. On Sunday mornings, there’s hardly anyone in the pattern and he was able to use a very wide 9,000’ runway for his taxi tests. The ground runs eventually turned into Spruce Goose hops and he did a number of those, becoming comfortable with the slow speed control. Though he felt confident of his ability to handle the Cozy in ground effect, he still wanted to shoot a few landings in a Cozy with someone beside him. One of the astronauts, Ken Cameron, had a Cozy. He’s a former Naval aviator and very precise in his flying. Ken allowed Dennis to shoot a few landings from the right seat and wished him the best. On a clear Sunday morning, when Dennis pretty much had the airport to himself, he lifted off in his 20-years-in-the-making Cozy. “I was advised not to do too much on that first flight and I didn’t,” he said. “I went to pattern altitude, got used to slow flight, was cleared to land and did just that. It wasn’t anywhere near the transcendental experience I had been led to expect and that I suspect many pilots feel.” He rated the first flight as an experience in “moderate anxiety”. His only squawk from the flight was a pitch trim system that needed stronger springs. That was corrected and he began logging some serious time. Today, he’s got over 150 hours of Cozy time that he’s enjoyed, a lot of it with his wife and friends. “I don’t think I’ve got another airplane in me,” he said. “But I like the Lancair Legacy, and if I had the money, I’d sure be tempted.”

In winning the Grand Champion Plans Built Award, Dennis admits there were “a lot of beautiful airplanes to choose from. I’d always thought that no matter how good yours is, there’s always going to be someone with something better.” Not this year. The judges were really impressed with Dennis’ attention to detail and the finish on his Cozy III. Between the Silver last year and the Gold this year, he added wheelpants and tended to a number of details that put him over the top. If the Grand Champion Award dates back to the first EAA Convention in 1953, Dennis is still in a very rare group of honorees. |

Aircraft Spruce Australia

Aircraft Spruce Australia